Celebrating Söre Popitz, the Bauhaus’ Only Known Woman Advertising Designer

First published on AIGA Eye on Design, March 2019. Forthcoming publication in Baseline Shift, ed. Briar Levit, published by Princeton Architectural Press, 2021

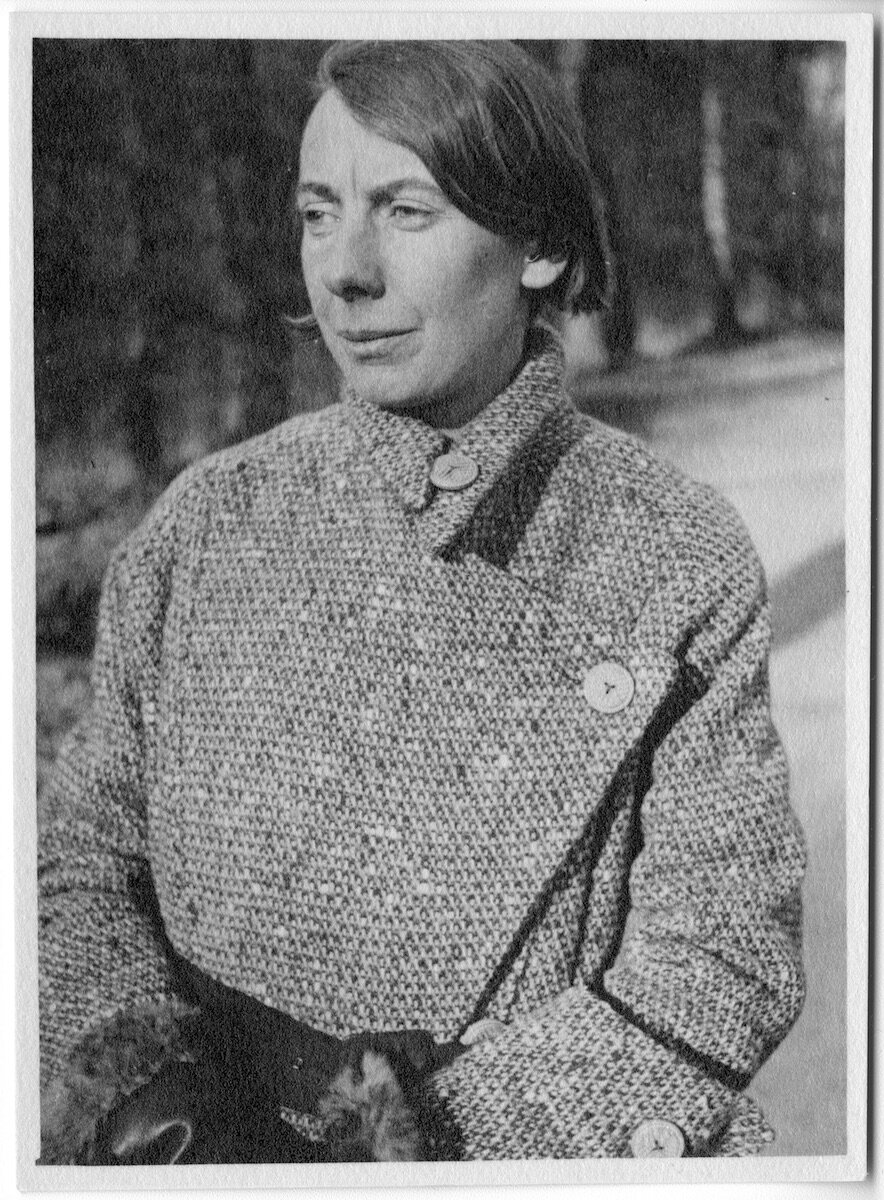

Portrait of Irmgard Sörensen-Popitz, 1924. Silver gelatin print, 12.2 x 9 cm. Bauhaus Dessau Foundation I 44190 / loan from Wilma Stöhr.

In Germany during the 1930s, there was one lifestyle magazine that every young woman had to have. An essential for those donning flapper skirts, cropped haircuts, and dramatic eyeliner, Die neue Linie first appeared on the newsstands in 1929 with a sensational lowercase title on its cover and articles on everything from fashion and home decor to sports. Art directed by former Bauhaus master Herbert Bayer—and featuring work by László Moholy-Nagy and Walter Gropius—the stylish women’s monthly was as modern as it came. Working on the magazine alongside those celebrated men of modernism was one lesser-known designer: she went by the name of Söre Popitz.

Born Irmgard Sörensen in 1896, Popitz is the only woman known to have pursued a career in graphics after studying at the Bauhaus. The designer and artist passed away in 1993 at ninety-seven; her life encompassed nearly the entirety of the twentieth century. When she first began freelancing in the 1920s, it was almost unheard of for a woman to work in advertising design and art direction. Through a unique set of circumstances, Popitz slipped through a crack and into the field of commercial arts, learning her craft from the originators of German modernism and going on to pursue her own career.

When Popitz enrolled as a student at the Weimar Bauhaus in October 1924, she’d just completed seven years of training at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Leipzig. There, she had studied under the seminal modernist type designer Jan Tschichold and was one of only a handful of women permitted into the school. By the time she had moved on to the Bauhaus, that school had progressively allowed women into the classroom, though women were encouraged to pursue weaving rather than the male-dominated mediums of painting, architecture, and typography. Popitz enrolled with the hope of meeting kindred spirits and participated in the school’s first-year preliminary course, taught by Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers. She left after only two semesters, never reaching the point in the curriculum where she would likely have been ushered away from graphics and into the weaving workshop.

It was because of this early turn of events that Popitz was ultimately able to succeed in an industry where other women struggled to get a foot in the door. It’s not completely clear why Popitz didn’t continue studying at the Bauhaus when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau at the end of her second semester. Reading between the lines of her diary, held at the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation archive, it seems likely that she didn’t align herself with the school’s new motto: “art and technology—a new unity.” Nevertheless, when Popitz moved back to Leipzig to set out on her own, she brought her Bauhaus training to commissions for publishers, household appliance companies, and other local businesses. Although many of her commercial designs bear the unmistakable influence of her male modernist mentors, Popitz embellished her work with blocky characters that represented a range of female experiences, lending her designs a distinctively feminine sensibility.

“Since I Could Think”: Söre Popitz’s Early Years

Söre Popitz, advertisment for Thügina, 1925/1933. Proof on paper, 14.9 x 12.5 cm. Bauhaus Dessau Foundation I 44143 / loan from Wilma Stöhr.

It was Popitz’s grandmother who first inspired her to pick up a paintbrush, according to the designer’s diary. “I am often asked, ‘Since when have you painted?’ Answer: ‘Since I could think!’” she writes, going on to describe her painted illustrations for her grandmother’s folktales. As a teenager in Kiel, Germany, Popitz attended the city’s craft college. Then in 1917 she decided to fully commit to a career in advertising draftsmanship and moved to Leipzig to attend the Academy of Fine Arts. A class photograph from the time shows her and a few other women peeking out from a dense hedge of suits.

According to Steffen Schröter, a Bauhaus Dessau Foundation staffer who researched Popitz’s estate, Academy of Fine Arts professor and graphic artist Hugo Steiner-Prag was responsible for opening the academy’s enrollment to women. Steiner-Prag’s stance, however, was heavily disputed by his colleagues, and it took Popitz two application cycles to receive a placement.

Once Popitz had finally enrolled, her work quickly caught the attention of the local design community. Her designs were displayed in an exhibition of advertising art, and in 1920 she won a prominent poster competition. The style of her pieces was in keeping with the period’s decorative, flamboyant illustration, though Popitz’s figures reveal a level of abstraction, pointing toward the stripped-backed, linear aesthetic that she would later embrace along with her fellow Bauhauslers.

During her studies at the academy, Popitz became acquainted with Tschichold and sat in on his lectures. Art historian Patrick Rössler notes the pivotal influence of the 1923 Weimar Bauhaus exhibition on the young designer: visiting the show in person, Popitz was apparently struck in particular by Moholy-Nagy’s typographic work, furthering her initiation into modernism. When she graduated from the academy in 1924, she married the Leipzig-based physician and anthroposophist Friedrich Popitz. But her curiosity about modern design had been piqued, and she became increasingly interested in the Bauhaus, as its reputation for experimental design pedagogy continued to grow. Popitz set off to Weimar to find out more. “I went to the Bauhaus because I was keen to meet like-minded people,” she wrote in her diary.

Material Sculptures: Student Life at the Bauhaus

All students at the Bauhaus received a year of basic training as part of their preliminary course, during which they experimented with color, shape, and materials. While Popitz was a student in Weimar, the course was team-taught by Moholy-Nagy and Albers. Moholy-Nagy focused on construction, balance, and materials, while Albers taught craft techniques. During one of Moholy-Nagy’s workshops on balance and the visual principles, Popitz created a study from glass, wire, metal, and wood, structured so that two black cubes and a white beam appear to float in space. A few years later, Moholy-Nagy published a photograph of her piece in his seminal book, From Material to Architecture, and it subsequently became an iconic example of the school’s pedagogy.

Söre Popitz, poster for Bode Gymnastik, 1925/1930. Poster paper, 44.9 x 59.8 cm. Bauhaus Dessau Foundation I 44251 / loan from Wilma Stöhr.

In her diary, Popitz writes only briefly about her time studying under Moholy-Nagy: “Yesterday I had to complete what Moholy buried us in. He wants the highest aim to be the mathematical calculation of form. For example, balance is calculated mathematically by so much red, so much blue, so much yellow....Art and mathematics must become one and the same, uniting in such a way that there is no ‘art per se’ any more. This has given me something to think about.”

Tellingly, she concludes her diary entry with the declaration that she doesn’t have to busy herself with this philosophical question about the new direction of art because “no woman can have anything to do with art.” Her statement reveals the patriarchal stranglehold still dissuading women from intellectual and artistic pursuits, despite the increasingly inclusive politics of the more progressive schools.

As part of the preliminary course at the Bauhaus, students attended color theory lectures by Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. Popitz’s abstract paintings during her time in Weimar—and also later in her life—bear the unmistakable influence of Klee’s artistic sensibility.

“The lessons with Klee, the color seminar with Kandinsky, and the material sculptures with Moholy-Nagy were all very important to me. But I could not join in with the Bauhaus’ next developments,” she wrote cryptically in her diary.

Designing New Lines: Freelancing in Leipzig

On returning to Leipzig in 1926, Popitz printed business cards that described herself as a specialist in “advertising design.” One early commission was an ad for a local gymnastics studio run by her close friend Charlotte Selver. The poster’s concise lettering on a clear, geometric grid seems to splice together a Tschicholdian approach to typography with the forms used by Moholy-Nagy and Bayer for Bauhaus communications.

Söre Popitz, advertisment for Thügina, 1925/1933. Proof on paper, 15 x 12.7 cm. Bauhaus Dessau Foundation I 44148 / loan from Wilma Stöhr.

It’s especially clear how formative Popitz’s brief time at the Bauhaus had been when looking at the stripped-back, linear ads she produced for a household appliance company named Thügina. Popitz’s series depicts different figures standing beside Thügina’s sinks and stoves—a stick-figure doctor, a husband and wife, a group of girls. Further ads feature a range of different types of women, from young girls in patterned dresses to housewives in aprons and lean figures dressed in stylish frocks, feathered hats, and glamorous earrings.

These playful, geometric stick figures recall the costumes in Bauhaus professor Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet. The household appliances on each poster are drawn in elegant, thin black lines and lack detailing, which, along with the unfussy typography, communicate cleanliness and efficiency. Everything about these designs would have conveyed modernity, functionality, and simplicity—ideal for modern consumers with their newly electronic, gas-heated, fully-functioning apartments. And Popitz’s stylish stick women, rendered abstractly, ranged from the traditional to the modern, appealing to housewives and working women alike.

Söre Popitz, brochure cover for the publisher Otto Beyer, presumed 1934. 21 x 15 x 0.2cm. Bauhaus Dessau Foundation I 44165 / loan from Wilma Stöhr.

As a freelancer, Popitz worked with the Leipzig publishing house Otto Beyer, which published Die neue Linie—a collaboration she would continue for twenty years. One of her most technically impressive designs for the publisher was a 1935 advertising brochure that places a woman’s face amid a field of embossed figures; her use of photomontage mirrors Moholy-Nagy’s (Popitz likely experimented with the technique as a student in the Bauhaus’s preliminary course). It’s a sophisticated piece of design, employing silver foil, die-cut letters, and delicate embossing onto its light paper. As in her Thügina ads, each delicately rendered female figure is dressed in a different outfit, from an apron to a schoolgirl’s skirt to a fashionable evening dress. What all the figures have in common is the large publication that they hold open in their hands. With the design, Popitz suggests that all women can read and see themselves in Otto Beyer. The multiplicity of her figures attempted to reach not an everywoman, but every woman.

It was through working with Otto Beyer and her acquaintance with Herbert Bayer that Popitz advised on the relaunch of the firm’s flagship women’s magazine under the name Die neue Linie, which translates to “the new line.” The cover of its first issue featured a photomontage by Moholy-Nagy depicting a woman in a fur coat looking out of a large, glass lattice window toward a mountain range. Moholy-Nagy’s cover linked the modern architecture of the times—with its emphasis on dramatic glass windows—to the style of the new, modern woman. The “new line” of the magazine’s name referred to modern design as much as it did to the new female silhouette. As Patrick Rössler reports, Popitz likely put Otto Beyer in contact with her former teacher for the commission.

Popitz’s own commissions for the magazine ranged from illustrations and collages to the design of the back cover, as well as advertising pages in which type treatments are merged with tiny spot drawings. She created just one front cover for Die neue Linie, in August 1931, and her photomontage clearly gestures back to Moholy-Nagy’s inaugural cover in its use of a mountain range background. In front of a landscape of snow-topped peaks, an illustrated woman with stylish cropped hair and a cap stands on a platform. This balcony, with its three thin, horizontal poles against a white wall, instantly recalls the design of the balconies lining the white-walled student dorms of the Bauhaus building in Dessau, which Popitz had visited a few years prior. The inclusion of this distinctly modern architectural detailing was especially fitting for the issue, as it featured an article by the Bauhaus’s first director and Dessau building architect, Walter Gropius.

Söre Popitz, cover for die neue linie, issue 12, 1931. 37 x 26.9 cm. Bauhaus Dessau Foundation I 44174 / loan from Wilma Stöhr.

Real Pictures: The War and Postwar Years

Otto Beyer remained Popitz’s sole employer during Germany’s National Socialist years. To better tolerate the hardships of wartime life, Popitz turned to decorative painting. She drew flowers, detailed self-portraits, and other politically harmless illustrations, writing in her diary that she lacked any inspiration for “real pictures.”

At the beginning of the Nazi regime, Popitz attempted to hide all of her Bauhaus studies in the basement of her husband’s medical office, yet they were still destroyed, during the bombing of Leipzig. The majority of her early work was lost, and what exactly she produced for Otto Beyer during the war years remains a mystery, as the publishing house was heavily damaged as well. Steffen Schröter notes that due to all these losses, the true scope of Popitz’s commercial output will forever remain unknown.

After the Soviet occupation of East Germany, Söre and Friedrich Popitz fled to Frankfurt am Main. Friedrich died only a few months after their escape. From 1949 onward, Popitz worked as a draftsperson for the Schwabe publishing house, a branch of Otto Beyer, and seems to have stopped pursuing work in advertising. For the next half of her life, her largest body of commercial work was the design of a number of patterns for Insel-Bücherei, a book series where each title is wrapped in an abstract background.

Browsing any secondhand bookstore in Germany today, you’ll find piles of the ubiquitous Insel-Bücherei series in dusty corners, and it’s within these stacks that you’re most likely to come across a design by Popitz. Her patterns from the 1950s and ’60s depart from her previous style and feature dense, expressionistic tangles of leaves, wispy brushstrokes, and deep blue waves of solemn paint. What was once modern must have seemed long ago.

When Popitz died in 1993, her estate went to the Wuppertal gallery, which later handed it over to the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation as a loan in 2011. Thank you to the Foundation’s inventory staff and especially Steffen Schröter, who shared his thesis on Popitz with me for the purpose of this article. All translations are my own. And many thanks to Max Boersma for his input.